Monkey Model for Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Identified at UC Davis Primate Center

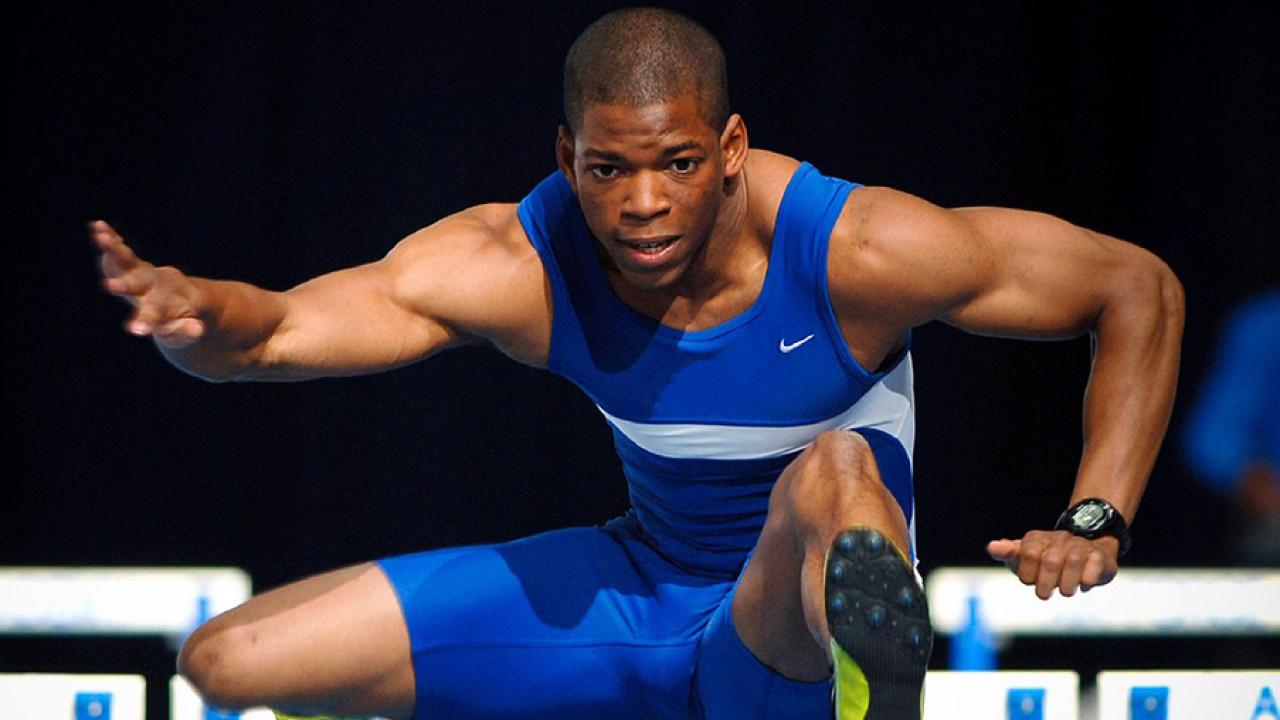

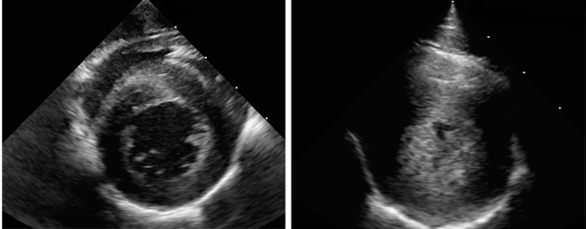

Monkeys and humans are similarly affected by deadly heart disease A collaboration between a team of pathologists from the California National Primate Research Center (CNPRC) and a cardiologist from the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine has resulted in the identification of an HCM (Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy) disease model naturally occurring in genetically related rhesus macaques in the CNPRC colony. This finding is considered to be crucial for research into early diagnosis and potential treatments for HCM in both monkeys and humans. CNPRC Pathologists Don Canfield, DVM, and Ross Tarara, DVM, DACVP, PhD, first identified an abnormality called left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) as a cause of sudden death in monkeys at the CNPRC beginning in 1992. The increasing prevalence of LVH in the California Center rhesus colony, particularly since 2000, has triggered a closer look at this disease and how the rhesus macaque may be used as an animal model for investigating HCM in humans. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy is a relatively common inherited disease that affects over 1 in 500 people in the general population, (conservatively estimated to be 700 – 725K in the US). It results in dramatic thickening of the left ventricle of the heart without any underlying cause. HCM often goes undiagnosed, but for a small number of people it can have serious consequences ranging from sudden death to irreversible heart failure. It is the most common cause of cardiac-related sudden death in people under 30 years of age, particularly young athletes. Many people have no symptoms or significant health problems, and the first symptom, cardiac arrest, may be the last. Sudden cardiac death in young, fit adolescents/ young adults is an unexpected tragedy – a 14-year-old boy died after collapsing at football practice; a 16-year-old high school basketball star collapsed and died after making his team’s game-winning basket; a 17-year-old rugby player died after a ball hit him in the chest. Each year, nearly a dozen college athletes in America die of sudden cardiac arrest, per NCAA estimates. The NCAA has chartered a new study to assess the feasibility of screening every Division I athlete for heart abnormalities that trigger the trauma. The findings could alter the NCAA's policy on physical examinations for college athletes. Many attempts have been made to detect those at risk for sudden cardiac death before playing sports; however pre-participation physicals appear to be of limited value in the diagnosis of underlying cardiovascular abnormalities. Although some patients may have an audible heart murmur, for most auscultation of the heart with a stethoscope does not detect any abnormality and an ultrasound exam is currently the only method to visualize the disease. Until recently, veterinarians at the Primate Center were unable to identify affected animals prior to their sudden death, slowing investigation of the disease. But in 2015, in collaboration with cardiologist Josh Stern, DVM, PhD, DACVIM, from the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, targeted screening was initiated using echocardiography on animals living in outdoor-housing. Using this method, monkeys within the colony have been recently identified with LVH. Work is now being conducted to identify genes that may be responsible for LVH in rhesus monkeys.

“The opportunity to study HCM and sudden cardiac death in the monkey represents a remarkable opportunity as all other animal models of HCM are fundamentally flawed. The results of these studies have the potential to significantly impact monkey and human health. This research highlights the true value of comparative medicine and the “one health” approach in science and medicine” emphasizes Dr. Stern.

CNPRC pathologists published the analysis of 20 years of findings on sudden cardiac death in the CNPRC rhesus monkeys in the prominent journal Comparative Medicine (April 4, 2016): “Left ventricular hypertrophy in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) at the California National Primate Research Center (1992 – 2014)”. Reader JR, Canfield DR, Lane JF, Kanthaswamy S, Ardeshir A, Allen AM, Tarara RP. Comp Med 2016;66(2):162-9. CNPRC pathologists and clinicians are also collaborating with the Yerkes National Primate Research, Oregon National Primate Research Center, and the Wisconsin National Primate Research. Other investigators and staff at the CNPRC participating in the HCM study included Rachel Reader, DVM, PhD, DACVP, Jennifer Lane, DVM (now at Washington National Primate Research Center), Amir Ardeshir, DVM, Sree Kanthaswamy, PhD (now at Arizona State University), and Mark Allen. Over a 21-year period, more than 160 cases of idiopathic LVH have been identified at the CNPRC, including 70 animals whose sudden death was attributed to LVH. Initial analysis of the pedigrees of affected animals strongly suggests a genetic basis for the disease. The presence of severe thickening of the wall of the left ventricle and the clinical presentation of sudden death suggests this disease has striking similarities to HCM in humans. Screening of living family members of affected animals has identified additional cases of LVH in the colony. While the nonhuman primate disease has some differences to the human disease, it continues to represent a valuable tool for investigating mechanisms behind cardiac hypertrophy, since in HCM the thickening of the heart muscle occurs without obvious cause. Furthermore, the ability to identify a population of macaques living with LVH could allow pathophysiology and potential treatments to be evaluated. This important research has highlighted the critical role that veterinarians play in identifying disease phenotypes in animals that may have comparable medical conditions to humans. The California National Primate Research Center is supported in part by the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (ORIP) of the National Institutes of Health through Award Number P51OD011107.