Early HIV infection and potential therapeutic targets

What is potentially exciting about this research is the demonstration that the early stages of gut inflammation and damage can be intervened by the targeted probiotic bacteria.

The mucosal lining of the human gastrointestinal tract is on the frontline of immune defenses, crucial in preventing infection and controlling the spread of intestinal pathogens. It must respond rapidly to eradicate pathogens, while simultaneously maintaining tolerance to commensal bacteria. This balance is critical to the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis.

When an individual is first infected with HIV, the virus causes a breach in the mucosal defense and the gut goes through a series of responses that lead to deficiencies in the immune system and defects in the epithelial barrier, which result in chronic inflammation, disease progression, and an increased susceptibility to pathogens. In HIV-infected individuals, systemic immune activation is also increased through a translocation of intestinal microbial products into the systemic circulation.

The biology behind this breakdown in the integrity of the gut barrier has been well studied, but what happens before this cascade of events was not understood until the following research study, conducted at the California National Primate Research Center (CNPRC) at UC Davis.

Dr. Sayta Dandekar, Core Scientist in the CNPRC Infectious Disease Unit, is using the rhesus monkey model of HIV, Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV), to investigate the early state dysfunction in the gut mucosal response and to determine the mechanisms contributing to the inability of the host to control these infections. This knowledge will be crucial in identifying therapeutic targets for mucosal protection against the virus and co-infections.

To conduct her research, Dr. Dandekar teamed with investigators from the CNPRC Department of Primate Medicine and from across UC Davis – Departments of Medical Microbiology & Immunology, Molecular and Cellular Biology, Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine, and Food Science and Technology. The research results were published in August 2014 PLoS Pathogens (“Early mucosal sensing of SIV infection by paneth cells induces IL-1β production and initiates gut epithelial disruption”).

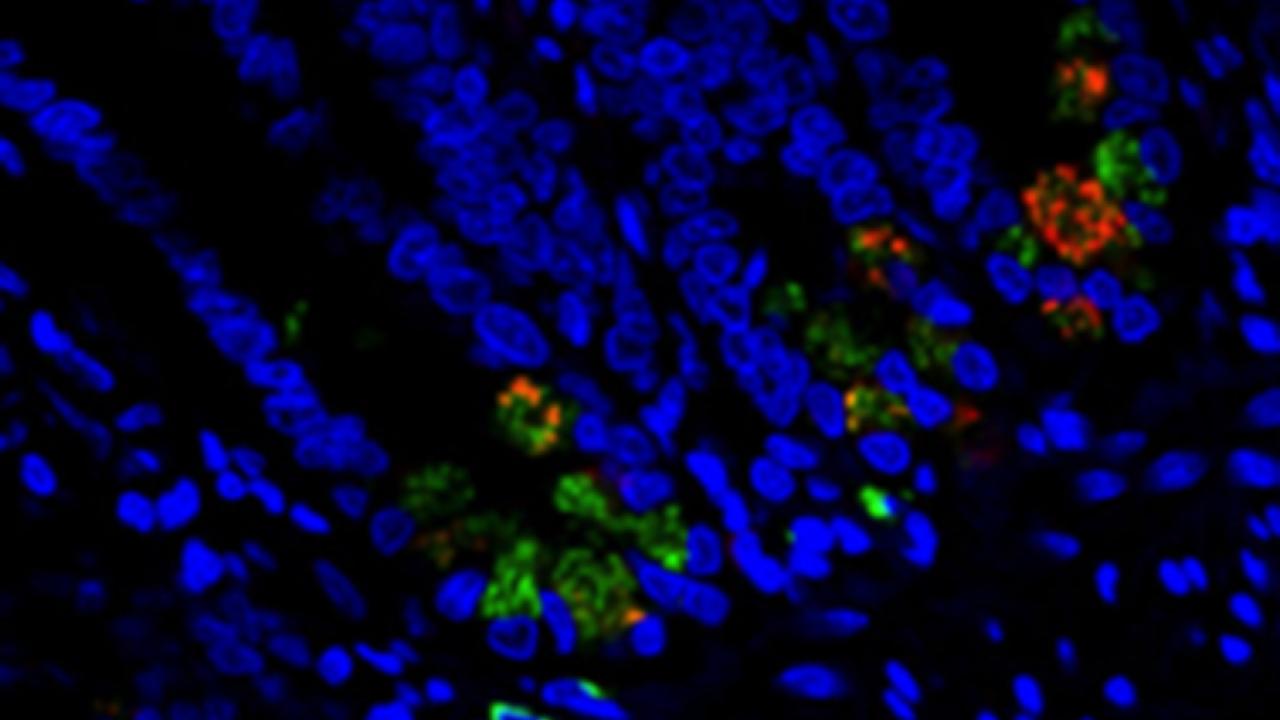

A focus of the investigation was Paneth cells, an integral part of gastrointestinal tract immunity. Paneth cells are one of the principal cell types in the epithelial lining of the small intestine and play a crucial role in epithelial cell renewal, immunity and host-defense, and produce antimicrobial substances that have been shown to have a significant effect on bacteria. While the mechanism by which Paneth cells sense and respond to pathogenic bacteria is well characterized, our understanding of their response to HIV infection is limited.

Dr. Dandekar’s research has shown for the first time that Paneth cells play a key role as the earliest detectors in sensing and responding to the virus and first line responders in setting the stage for the induction of gut inflammation. In animals infected with SIV, the presence of virus within gut epithelium is co-localized with Paneth cells. Moreover, Paneth cells appeared to respond to the virus by producing interleukin-1β, an important mediator of the inflammatory response.

This study highlights the need for future investigations to determine the mechanisms of Paneth cell sensing and response to viral infections, and to clarify the importance of the gut epithelium in HIV infection. Understanding is sought for the gut epithelium as not just a target of disease but also as initiator of immune responses to viral infection, which can be strongly influenced by commensal bacteria.

Another focus of the study investigated for the first time the immune response by the gut mucosa to commensal bacteria (such as Lactobacillus plantarum) in the context of early HIV infection. The researchers found that the host maintains its ability to distinguish pathogenic (S. Typhimurium) and commensal bacteria and mount the proper immune response.

The research findings also suggest a supportive role of commensal bacterium L. plantarum in overcoming SIV-induced gut inflammation and epithelial disruption, raising the possibility of using L. plantarum to intervene the early mucosal-viral interactions that may influence gut inflammation. In addition to its anti-inflammatory effects, they observed enhanced recruitment of T helper 17 cells (which can give rise to protective cells) in response to L. plantarum, suggesting a supportive role of L. plantarum in overcoming SIV-induced gut inflammation and epithelial tight junction disruption. This recruitment of T helper 17 cells may have a role in epithelial repair.

What is potentially exciting about this research is the demonstration that the early stages of gut inflammation and damage can be intervened by the targeted probiotic bacteria.

However, the findings also discovered unintended consequences that an L. plantarum probiotic therapeutic adjuvant may include the establishment of silent viral reservoirs. The results raise an important consideration in the development of probiotic therapies for HIV infection, and highlight the need for a better characterization of probiotic bacterial functions and effects.

By understanding the mechanisms that underlie the host / microbiota relationship in health and HIV disease, it will be possible to capitalize on their evolved synergy while identifying gaps in mucosal defenses that can be fortified through therapy.

Hirao LA, Grishina I, Bourry O, Hu WK, Somrit M, Sankaran-Walters S, Gaulke CA, Fenton AN, Li JA, Crawford RW, Chuang F, Tarara R, Marco ML, Bäumler AJ, Cheng H, Dandekar S. Early mucosal sensing of SIV infection by paneth cells induces IL-1β production and initiates gut epithelial disruption. PLoS Pathog. 2014 Aug 28;10(8)

Photo caption: Within the first two days of human immunodeficiency viral invasion in the gut, specialized cells in the intestine called Paneth cells (Lysozyme A -green) produce the cytokine interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β - red), causing inflammation and compromising the integrity of the protective epithelial intestinal layer.