Breast- and Bottle-fed Infant Monkeys Develop Different Immune System

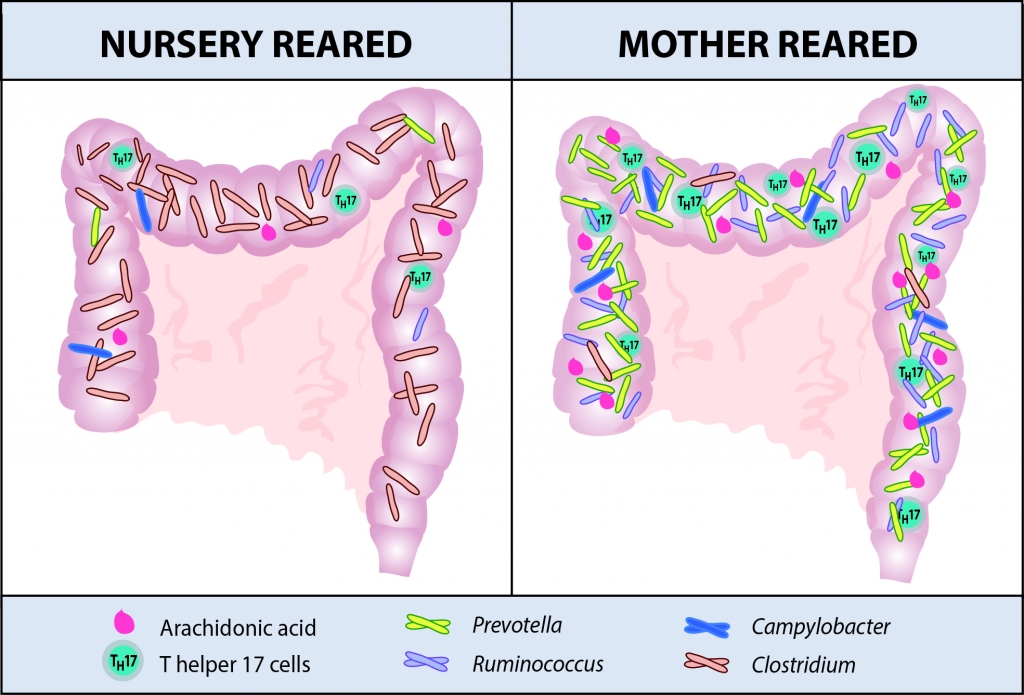

In a study published in Science Translational Medicine on September 3, 2014, researchers from the California National Primate Research Center (CNPRC) at UC Davis and from UC San Francisco have shown that breast-and bottle-fed infant rhesus macaques develop different immune systems. Although the researchers expected that different diets would promote different intestinal bacteria, they were surprised at the extent to which these bacteria were found to shape immunologic development. Breast-fed macaques had more “memory” T cells and T helper 17 (TH17) cells, which are known to fight Salmonella and other pathogens. Surprisingly, these differences persisted for months after the macaques had been weaned and placed on identical diets, indicating that variations in early diet may have long-lasting effects. “We saw two different immune systems develop: one in animals fed milk and another in those fed formula,” said Dennis Hartigan-O’Connor, a scientist in the CNPRC’s Infectious Diseases Unit and its Reproductive Sciences and Regenerative Medicine Unit, and assistant professor in the Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology at UC Davis. “But what’s most startling is the durability of these differences. Infant microbes could leave a long-lasting imprint on immune function.” Previous research has highlighted the relationship between breast milk, microbiota and the developing immune system. For example, sugars in breast milk help grow specific bacteria, which in turn support certain immune cells. This new study is an important step towards understanding how these separate pieces link together and how they might influence responses to infections or vaccinations. Macaques are born with virtually no TH17 cells, and must develop them during the first 18 months of life. Hartigan-O’Connor and other researchers have noted that some macaques develop large TH17 populations, while others have few such cells. This could profoundly affect the animals’ ability to fight infection. To understand this variability, CNPRC investigators Hartigan-O’Connor, Amir Ardeshir, Nicole Narayan, Gema Mendez-Lagares, Ding Lu, and Koen K. A. Van Rompay, and researchers from UC San Francisco followed six breast- and six bottle-fed rhesus macaques from five to 12 months of age. At six months, they found significant differences in the two groups’ microbiota, as was to be expected in animals receiving different diets. Specifically, the breast-fed macaques had larger numbers of the bacteria Prevotella and Ruminococcus, while the bottle-fed group had a greater abundance of Clostridium. Overall, the microbiota in breast-fed macaques was more diverse than in the bottle-fed group, measured by analyzing stool samples. The surprise came when these researchers examined the immune systems of the two groups. By 12 months, the groups had significant contrasts in their immune systems, with the differences centered on T cell development. The breast-fed group showed a much larger percentage of experienced “memory” T cells that are more able to secrete immune defense chemicals called “cytokines”, including TH17 cells and immune cell populations making interferon. This is the first time researchers have shown these immunologic characteristics may be imprinted in the first few months of life. “This study suggests the gut microbiota that are present in early life may leave a durable imprint on the shape and capacity of the immune system, a programming of this system if you will,” said Ardeshir. Further investigation suggested possible chemicals that may drive key differences between the two groups, including arachidonic acid, which stimulates the production of TH17 cells and is found in macaque breast milk. This chemical was tightly linked to TH17 cell development and previous studies have suggested that it can influence T cell development. The researchers caution, however, that all the chemicals identified in this study must be tested in larger studies specifically designed to understand their effects.

While this research provides a fascinating window into immune cell development in macaques, Hartigan-O’Connor cautions that it doesn’t prove the same mechanisms exist in people. The lab is planning similar studies in humans to test that hypothesis. In addition, this research does not prove a link between breastfeeding and better health. There’s a developmental shape to the immune system that we don’t often consider,” Hartigan-O’Connor said. “It’s dramatic how that came out in this study. There’s a lot of variability in how both people and monkeys handle infections, in their tendency to develop autoimmune disease, and in how they respond to vaccines. This work is a good first step towards explaining those differences.” Research projects such as these demonstrate how taxpayer and donation dollars are put to work and are leading to new diagnostics, therapeutics, and clinical procedures that enhance quality of life for both humans and animals. Other authors include: Marcus Rauch, Susan V. Lynch and Yong Huang at UC San Francisco. This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (K23AI081540), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation under a Grand Challenges Exploration award (#52094) and by Office of the Director of NIH (P51-OD011107). A. Ardeshir, N. R. Narayan, G. Méndez-Lagares, D. Lu, M. Rauch, Y. Huang, K. K. Van Rompay, S. V. Lynch, D. J. Hartigan-O’Connor, Breast-fed and bottle-fed infant rhesus macaques develop distinct gut microbiotas and immune systems. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 252ra120 (2014).