SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for the disease referred to as COVID-19, has swept across the world infecting millions of humans and tragically killing a significant proportion of those infected. COVID-19 has grown from an outbreak to an epidemic and finally a worldwide pandemic at a historic rate. To combat the virus and resulting disease, infectious disease researchers world-wide have had to act just as fast. In an attempt to understand what it is like inside the lab we sat down with one of our infectious disease researchers here at the California National Primate Research Center (CNPRC).

First off, could you introduce yourself?

I’m Smita Iyer, I’m an assistant professor in the department of pathology, microbiology, and immunology. I moved to UC Davis about three and a half years ago. I’m an immunologist, my lab studies T-cells and we focus on understanding the role of T-cells in protective antibody responses to viral infections and we are also keen on understanding the role of T-cells in immunopathogenesis during viral infections.

What is it like to be an infectious disease researcher during an active pandemic?

In one way, we have been training for this moment. It is very heartening that we are able to gather as a team and use our skillsets to answer fundamental questions and contribute to our understanding of this deadly virus. It is also sobering in a way.

“We have had to essentially hit the ground running”

How has your work and laboratory practice changed as a result of COVID-19?

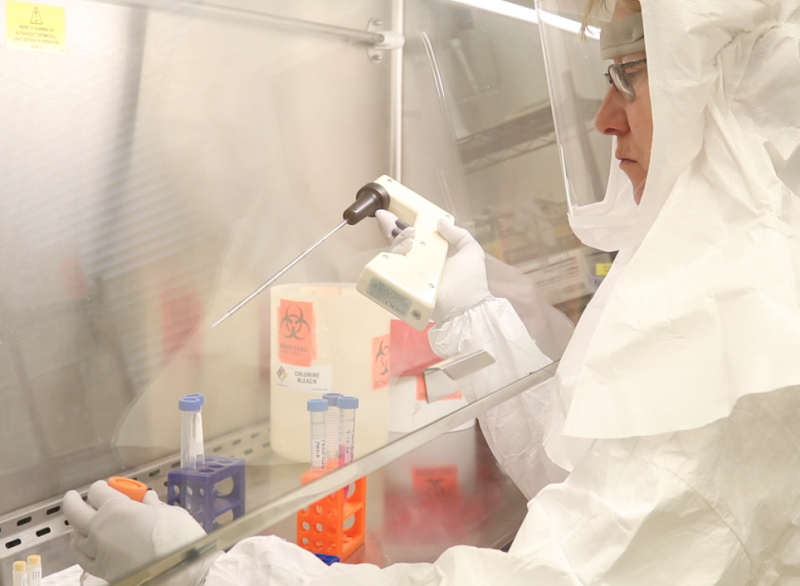

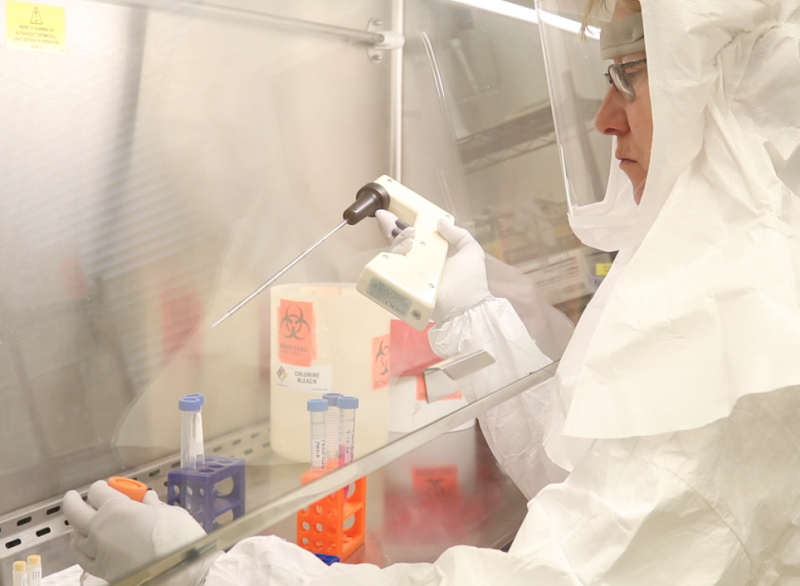

There has been a dramatic change in our lab. Our lab has been central to all of the SARS-CoV-2 work at the California National Primate Research Center (CNPRC). We have had to essentially hit the ground running. We have had to train to do work in Bio Safety Level-3 (BSL-3) which really requires a different mindset. I’m proud to say that all of my lab members have stepped up to the plate and performed extremely efficiently, quickly learning skills that they did not necessarily have.

Right now, my lab studies SARS-CoV-2, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), and Cytomegalovirus (CMV). All three are viruses. The way we have divided up the work is that we have dedicated personnel that are in the BSL-3 [laboratory] performing SARS-CoV-2 work and at the same time we have individuals dedicated to HIV and CMV work. We don’t forget about the other viruses.

There is a lot of equipment and specific facilities needed to do the kind of work you do. Could you speak a little bit about what is so special about doing your work here? And why there are so few facilities capable of doing this work?

You are absolutely right. For infectious disease research, first off you need the right animal model and the nonhuman primate model is one of the most robust of the animal models. Specifically, we work with rhesus monkeys. You know, if you take for example, the big three of infectious diseases, HIV, Tuberculosis, and malaria. Certainly, nonhuman primates are one of the most robust models for a variety of reasons. The three main reasons being the tropism of the pathogen itself, the distinct similarity in the immune makeup of rhesus monkeys to humans, and the remarkable similarity in anatomy and physiology of them major target organ systems.

“Most importantly, we need highly skilled, dedicated and trained personnel to run these studies, to collect samples, to process samples.”

In terms of equipment and facilities: you need housing for these animal models, you need specific housing for instance for SARS-CoV-2 you need BSL-3 facilities. Integral to these facilities is containment of aerosol. For something like SIV, the model for HIV, BSL-2 facilities work. So clearly you need adequate housing, you need specific housing for injected monkeys. You need a variety of equipment. If you think about it, it’s almost analogous to a doctor’s office. The vet staff here relies on equipment they need to ensure the animal is healthy and they can intervene should anything happen.

In terms of equipment and facilities: you need housing for these animal models, you need specific housing for instance for SARS-CoV-2 you need BSL-3 facilities. Integral to these facilities is containment of aerosol. For something like SIV, the model for HIV, BSL-2 facilities work. So clearly you need adequate housing, you need specific housing for injected monkeys. You need a variety of equipment. If you think about it, it’s almost analogous to a doctor’s office. The vet staff here relies on equipment they need to ensure the animal is healthy and they can intervene should anything happen.

Now add on to this another layer of complexity. We need highly, highly specialized equipment for research. In fact, it’s a constellation of powerful equipment from thermocyclers for PCR, flo-cytometers to obtain powerful information on the immune response and equipment for microscopy. The most important is we need highly skilled, dedicated and trained personnel to run these studies, to collect samples, to process samples. For instance, in addition to the BSL-3 facility that houses monkeys you need a BSL-3 facility to process the samples. We have one right next door [to the CNPRC] at the CIID (Center for Immunology and Infectious Diseases) and clearly you need dedicated personnel to analyze these data ultimately working collaboratively as a team to find meaningful solutions. So, it really takes a village and it takes a large amount of resources to do our job and do it really well. I can’t imagine doing what I’m doing anywhere else but the CNPRC.

Could you speak to why it’s so important to test these vaccines and do the immune work you do in nonhuman primates when they have already moved on to human trials?

Yes, so why do animal studies when you have a vaccine that is close to licensure? That is a really good question. Let me actually take a step back. The unprecedented time scale of the COVID-19 vaccine is, in part, due to an incredible investment over the past many, many decades in biomedical research. We are in the position we are now because of all the extensive funding and all the research that has happened in the monkey model and in the mouse model. We would not be in this position [quickly developing vaccines] without that.

“Animal models are absolutely critical if you want to make the vaccine better and target other infectious diseases.”

Going back to your primary question. Why test vaccines in animal models when you have signal of efficacy in human studies? The reason you would do this is to understand mechanisms of protection. For instance, the monkey model gives you an opportunity to titrate your challenge dose and ask questions to how efficacious your vaccine would be and secondly, how durable this protective immunity is. Given the invaluable opportunity lavage samples as well as tissue biopsies you can really understand the individual mechanisms by which the vaccine protects.

Why is this important? You can then harness those very individual mechanisms to then make the vaccine better or use the information for a virus such as HIV for which we do not have a vaccine. Animal models are absolutely critical if you want to make the vaccine better and target other infectious diseases.

“In fact, the CNPRC is unique in that we have one of the most well characterized aged and diabetic cohort of monkeys that are being taken care of by our incredible vet staff.”

The CNPRC has received funding for studies specifically focused on high risk groups. Could you discuss the importance of conducting research with a geriatric/aged population like we have at the CNPRC?

You raise a really important point. When you do clinical studies, you are limited in the kind of volunteers you can get and typically the most vulnerable and especially the regards to COVID-19 as we have seen are the elderly and individuals with pre-existing conditions such as type II diabetes and hypertension. It is unlikely that in a clinical setting, A. that you would get enough volunteers to really test the efficacy of the vaccine and B. to understand the extent of the immune function in this subset of individuals. We can specifically ask these questions in the rhesus model.

In fact, the CNPRC is unique in that we have one of the most well characterized aged and diabetic cohort of monkeys that are being taken care of by our incredible vet staff. This is a fantastic resource to really ask in depth questions about vaccine efficacy across the spectrum of population that is going to be vaccinated, and more importantly the most vulnerable that really need the vaccine.

What are some active studies you are particularly excited about?

A project that has been funded to John Morrison and myself. This is something that is going to be extremely important for two main reasons. One, this project asks the question, ‘what are the determinants of immune-pathogenesis in SARS-CoV-2?’ To answer this question, we will specifically focus on the aged type II diabetic rhesus monkey colony.

Another important question is, ‘What is the extent of neuroinflammation that you see following SARS-CoV-2?’ The brain is clearly not a target organ for SARS-CoV-2, but we have heard suddenly there is enough evidence now of side effects in the brain and we know that the inflammatory response following SARS-CoV-2 can affect the brain, the heart, and the liver.

“To be able to contribute in the lab and also public outreach is a privilege. Is it busy? Yes, but I think, again, it is what we do as scientists.”

I think these set of studies are going to be very interesting because they will allow us to focus on areas that have not received a lot of attention but could become extremely important as we move forward. The long-term consequences of inflammation in the brain, even following viral control and recovery from SARS-CoV-2, could have a substantial impact on the health of the recovered individuals.

Do you find yourself being pulled outside of the lab because this is an active pandemic? Is it difficult to manage your laboratory while also trying to address public health and communication?

I think it is an incredibly opportunity because ultimately science has a social mission. To be able to contribute in the lab and also public outreach is a privilege. Is it busy? Yes, but I think, again, it is what we do as scientists. It is heartening to be able to be able to showcase what we do to the public.

“Ultimately science has a social mission. To be able to contribute in the lab and also public outreach is a privilege.”

In record timing of less than a year, researchers like Iyer have managed the remarkable. Last month, the FDA granted emergency use authorization of two vaccines which are now being administered across the country. Despite the circulating vaccine there is still work to be done. Scientists are striving to understand the full extent of the virus’ effects on the human body as well as collecting information from this pandemic to aid with prevention and treatment of future diseases.

Written by Logan Savidge

lesavidge@ucdavis.edu

In terms of equipment and facilities: you need housing for these animal models, you need specific housing for instance for SARS-CoV-2 you need BSL-3 facilities. Integral to these facilities is containment of aerosol. For something like SIV, the model for HIV, BSL-2 facilities work. So clearly you need adequate housing, you need specific housing for injected monkeys. You need a variety of equipment. If you think about it, it’s almost analogous to a doctor’s office. The vet staff here relies on equipment they need to ensure the animal is healthy and they can intervene should anything happen.

In terms of equipment and facilities: you need housing for these animal models, you need specific housing for instance for SARS-CoV-2 you need BSL-3 facilities. Integral to these facilities is containment of aerosol. For something like SIV, the model for HIV, BSL-2 facilities work. So clearly you need adequate housing, you need specific housing for injected monkeys. You need a variety of equipment. If you think about it, it’s almost analogous to a doctor’s office. The vet staff here relies on equipment they need to ensure the animal is healthy and they can intervene should anything happen.